The false consensus effect describes how you overestimate how common your beliefs and actions are. This cognitive bias makes you treat your view as the norm and can be used as a lever in dark psychology to manufacture compliance.

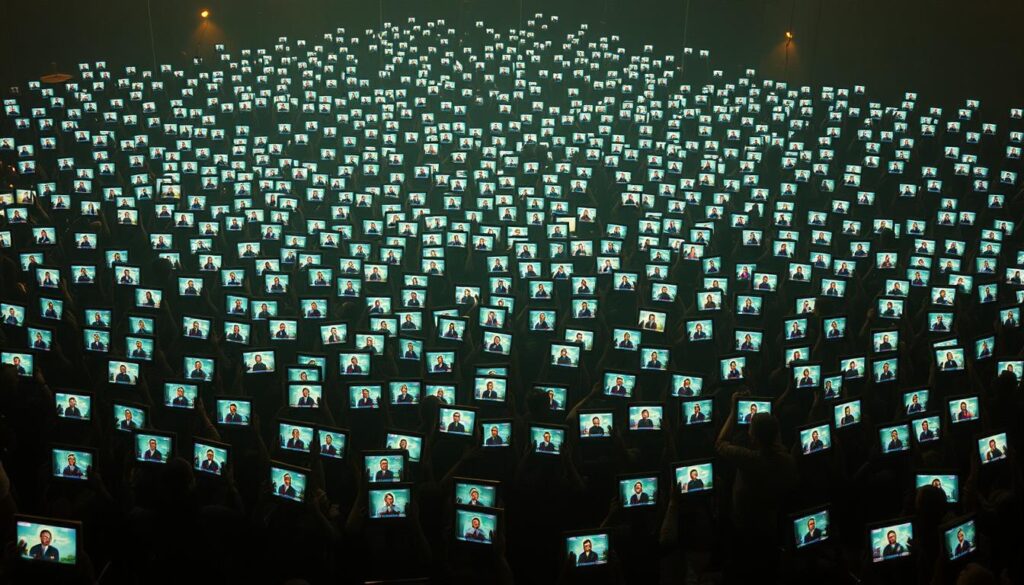

In social psychology research, people projected their own habits onto others, creating a misleading sense of majority. Manipulators amplify that projection to create an illusory majority, turning perceived consensus into pressure.

The consensus effect shows up in politics, marketing, and online groups where social proof drowns nuance. When you accept the crowd as truth, you stop checking facts and lose autonomy.

- Tactic: Frame dissent as risky to force compliance.

- Defense: Ask, “What is the base rate?” and verify data.

- Tactic: Inflate apparent numbers to simulate support.

- Defense: Trace claims to sources, not vibes.

Key Takeaways

- This bias makes you assume your view is common.

- It is exploited to create illusory majorities and pressure.

- Look for data and base rates before you conform.

- Expect shame or deviance framing when you resist.

- Perceived consensus often differs from real consensus.

Dark Psychology Primer: How Consensus Becomes a Weapon

A carefully staged sense of public agreement becomes a shortcut for control. When you see repeated claims that “most people” agree, you feel safer following the crowd.

Power lever: Inflate perceived norms to shrink resistance

Researchers like Ross et al. (1977) found people overestimate how common their choices are. Echo chambers and platform algorithms then magnify that overestimate.

“Your brain treats visible agreement as a risk reducer and a quick decision rule.”

Control tactic: Make dissent feel deviant and risky

Weaponization of consensus uses your herd instinct against you. Tactics include repetition, deviance labeling, testimonial floods, and bot amplification.

- Tactic: Repeat “most people agree” until it feels undeniably common.

- Tactic: Label dissenters as unsafe or fringe to raise social cost.

- Defense: Demand verifiable base rates and sample outside your bubble.

| Tactic | Purpose | Defense |

|---|---|---|

| Testimonial floods | Create apparent majority | Trace claims to sources |

| Deviance labeling | Shame dissenters | Separate dissent from threat |

| Social media seeding | Turn loud into large | Sample outside feeds |

What Is the False Consensus Effect?

You often assume others share your choices, making your personal view feel like a public norm.

This phenomenon, called the false consensus effect, is your tendency to see your opinion as widely shared. In social psychology and attribution, you treat your choice as the sensible one, so you expect others would choose it too.

Egocentric bias and social perception attribution

The bias stems from an egocentric bias: you project your beliefs onto others and downplay disagreement. In the first study Ross conducted, participants predicted that other people would make the same choice they preferred.

“Participants saw their choice as normal and judged opposite choices as deviant.”

The mechanism is simple: you use social perception attribution shortcuts. What felt right for you becomes the assumed norm.

- Takeaway: The false consensus makes you misread majority beliefs.

- Takeaway: Opposite choices often attract negative trait inferences.

- Practical: When someone claims “everyone agrees,” ask for numbers and sources.

| Concept | What it means | Quick defense |

|---|---|---|

| Perception attribution | You treat personal choice as normative for others | Request base rates and sampling details |

| Egocentric bias | You project beliefs onto people outside your circle | Survey diverse groups before concluding |

| Manipulator leverage | Claimed consensus removes need for persuasion | Verify claims; separate loudness from size |

Why Your Brain Defaults to “Everyone Is Like Me”

When you judge social reality, your brain leans on personal experience and fills gaps with projections. This mental shortcut explains why the false consensus effect often feels automatic.

Motivational drives and ego-defense

You protect your self-image by treating your choice as normal. This ego-defense reduces discomfort and makes dissent seem threatening.

Selective exposure and availability

You live near similar people and follow similar feeds. That clustering and memory availability inflate perceived agreement.

Ambiguity resolution and heuristics

In fuzzy situations you use your definitions. Simple heuristics turn vague cues into assumed norms, so manipulators can exploit language like “most” or “typical.”

Salience, focus, and logical processing

You focus on your stance, which fills the scene and crowds out alternatives. If you view a choice as situational, you still expect many other people to do the same.

- Tactic: Prime salience by repeating a view. Defense: Define terms precisely and ask for numbers.

- Tactic: Curate exposure to similar voices. Defense: Seek counterexamples beyond your circle.

These mechanisms link to attribution and broader attribution processes. Perception attribution processes and egocentric bias social combine to misread others’ behaviors. Watch how the consensus effect is used; then check sources before you accept what feels common.

Classic Experiments That Proved the Bias

Laboratory puzzles and public tasks exposed a reliable tendency: you overproject your own picks onto strangers.

Ross, Greene, and House: dilemmas and trait inferences

In the first study, participants read short dilemmas, predicted peer responses, chose their own answer, and rated personalities.

Across these paradigms, people overestimated agreement with their choice and made harsher attribution judgments about opposite choosers. These findings, which ross conducted and reported in the journal experimental literature, anchored this line of experimental social psychology.

“Eat at Joe’s” sandwich board: choice, prediction, and attribution

In the sandwich board studies, participants asked to wear sandwich board signs revealed split perceptions: 62% of those who agreed wear the sign believed others would too, while only 33% of refusers said the same.

That gap shows how public commitments inflate perceived endorsement and prime social pressure.

“When choices are visible, predictions quickly become a tool for social control.”

- Practical: Separate the act from the actor—don’t let attributions be weaponized.

- Defense: Ask, “From what sample and study?” before accepting claims about majority behavior.

Modern Frontiers: Echo Chambers, Social Media, and Polarization

Algorithms and social habits now amplify private views until they read like public truth.

Platforms and people combine to magnify agreement signals. Curated feeds, likes, and trending markers act as shortcuts that suggest wide approval.

Echo chamber dynamics compress dissent by repeating similar posts and rewarding engagement. That makes a small circle look like a large consensus.

Research snapshots and what studies show

Facebook data found users still see diverse viewpoints, but algorithms and self-selection bias what surfaces (Bakshy, Messing, & Adamic, 2015).

Other research shows biased feeds raise the perception that the public shares your position (Luzsa & Mayr, 2021).

Heavier social media use links to larger false consensus estimates across traits, though these links are modest (Bunker & Varnum, 2021).

“Exposure to favorably biased feeds increases the felt public support for one’s views.”

Power, control, and practical defenses

Manipulators seed narratives onto others using influencers, paid posts, and coordinated accounts. Timing and repetition during attention spikes create inevitability.

- Monitor: Diversify sources and inspect feed settings.

- Check: Log when your “everyone agrees” feeling rises and compare independent outlets.

- Resist: Treat visible engagement as signal, not base rate.

| Mechanic | How it inflates agreement | Quick defense |

|---|---|---|

| Curated feeds | Show more similar views, reduce dissent visibility | Follow varied accounts and mute algorithmic suggestions |

| Engagement signals | Likes and shares appear as social proof | Verify numbers and source samples before trusting reach |

| Coordinated seeding | Creates artificial momentum in short windows | Check timestamps, account types, and independent reporting |

False Consensus Effect

Your gut treats your own choices as the default, so you assume most others would pick the same.

The core law: what feels normal to you can distort your perception of what’s normal for everyone.

Ross et al. (1977) showed this bias in simple tasks. People judged alternative stances as deviant and assumed their picks were typical.

The manipulation angle is direct: amplify visible agreement and your mind fills in the rest. That is why manufactured consensus works—it taps a ready mental shortcut.

“This bias centers on seeing your stance as typical and treating alternatives as odd.”

- Treat every “everyone thinks” claim as a persuasion attempt, not a fact.

- Pause, verify, then decide—control follows the one who checks the claim.

| Core claim | How it reads | Quick check |

|---|---|---|

| Personal normalcy | You assume others mirror you | Ask for representative numbers |

| Manufactured signals | Visible agreement seems large | Trace sources and timestamps |

| Decision power | Perceived majority pressures choice | Delay action; seek outside samples |

Climate Change and the Mirage of Agreement

Climate debates often look like tidy majorities, but close inspection reveals deep misreading of who actually agrees.

Research shows both sides overestimate how many people share their views. Leviston, Walker, & Morwinski (2013) found people inflate the share that denies warming and downplay other positions.

This creates pluralistic ignorance: most privately reject an idea but assume others accept it, so a false norm persists.

Overestimation, underestimation, and pluralistic ignorance

Both camps project their own beliefs and read public opinion through that lens. You see loud testimonials and think they reflect general opinion, when often they reflect a small, vocal slice.

Manipulation angle: Polarize, then claim the majority

Actors polarize the issue, then present polls, lists, and testimonials as proof of a sweeping majority. That playbook uses repetition to shut down debate.

“Polarize first, then testify to inevitability.”

- Defense: Inspect methodology—sample size, wording, and timeframe matter.

- Defense: Separate scientific assessments from social media opinions.

- Takeaway: the phenomenon false consensus can be engineered around hot topics; verify before you accept a claimed majority.

Cross-Cultural and Ongoing Research

Cross-cultural work shows that what feels like a majority in one society can read very differently in another. New comparative studies probe how norms and identity cues change your read on public opinion.

Findings from Frontiers in Psychology

Frontiers in Psychology reports that projection rises when group identity is highlighted. Choi & Cha (2019) found stronger estimates of agreement when belonging was made salient.

Where the bias strengthens or weakens

Individualist settings tend to amplify your personal norm projection. Collectivist contexts shift perception: group rules shape what you assume most people do.

“In tight-norm cultures, penalties for deviance raise the cost of misreading social perception.”

- In tight societies, perceived consensus often looks larger.

- In loose or diverse settings, your projection can under- or overestimate real support.

- Ongoing research links networks and identity cues to changes in the consensus effect.

| Context | How it shifts estimates | Practical defense |

|---|---|---|

| Individualist cultures | Higher personal projection | Check diverse samples before assuming support |

| Collectivist cultures | Group norms bias reports | Ask local informants and verify local data |

| Tight-norm environments | Deviance penalties inflate perceived agreement | Look for silent minorities and independent surveys |

Practical takeaway: when you enter a new culture, your “what people think” meter is likely wrong. Verify with local research and avoid assuming home norms travel well.

How Manipulators Manufacture “Consensus” in the Wild

Coordinated narratives can make marginal views appear mainstream overnight. You need a concrete playbook to spot when control is being staged and when to push back.

Playbook: politics, marketing, and group persuasion

Actors exploit your natural shortcuts in psychology. Ross et al. showed people project their stance onto others, and platforms scale that bias.

Tactics to watch

- Astroturfing — fake grassroots pages and bots simulate consensus to sway undecided people.

- Testimonial floods — repeat “real customer” stories until volume looks like evidence.

- Influencer cascades — seed a script onto others with coordinated timing.

- Poll priming — push cherry-picked numbers to nudge the decision bandwagon.

- Echo chamber engineering — optimize feeds to trap you in approving loops.

- Visual counts — likes and shares used as perception levers, not ground truth.

Detection and defense

- Source-trace viral claims and demand poll methodology.

- Reverse-image testimonials and log who benefits from the push.

- Follow contrarian outlets and set timed cool-downs before a public decision.

“Control the signals, and you control what people judge as normal.”

Warning Signs You’re Being Nudged by False Consensus

When voices sync too neatly, you should ask who organized the chorus. False unanimity often precedes pressure to act quickly.

Rapid unanimity claims without verifiable data

Look for claims of broad support with no auditable links. If no methodology, sample, or source is given, treat the claim as suspect.

Shaming of out-groups and deviance framing

Watch for language that brands others as dangerous or fringe. Ross et al. (1977) showed people label alternatives as deviant and infer harsh traits about dissenters.

- Red flag 1: sudden “everyone agrees” claims without links to auditable data.

- Red flag 2: shaming language that brands others as fringe or dangerous.

- Red flag 3: identical talking points across accounts—coordination, not organic consensus.

- Red flag 4: appeals to people like you—identity-first, evidence-later messaging.

- Red flag 5: moving goalposts when numbers are requested—classic bias cover.

- Red flag 6: removal of comment dissent framed as “safety” rather than policy.

- Red flag 7: demands for speed—no time to verify fuels the false consensus effect.

Antidotes: log claims, capture screenshots, and check archives before you act. Ask, “What’s the base rate and how was it measured?”

| Red Flag | What it indicates | Quick defense |

|---|---|---|

| Unverifiable unanimity | Possible manufactured momentum | Request sources, timestamps, and sample details |

| Coordinated talking points | Scripted persuasion | Trace accounts and check originality of messaging |

| Shaming language | Deviance framing to silence dissent | Separate critique from safety; seek independent views |

| Speed pressure | Prevents verification | Impose a cooling period before deciding |

Defensive Countermeasures: Regain Autonomy and Choice

Regaining control starts with steps that force you to test what feels widespread against what is actually measured. Logical processing and salience can inflate perceived agreement; deliberate checks reverse that bias (Marks & Miller, 1987; Heider, 1958; Verlhiac, 2000).

Disconfirm your feed: Deliberate counter-exposure

Add credible sources that challenge your opinions. Follow journalists, academics, and outlets that disagree with you.

Rotate at least three independent outlets weekly to prevent echo amplification.

Precision checks: Ask “what is the actual base rate?”

Before any pivotal decision, get numbers: sample size, wording, and timeframe. Treat raw counts as claims to verify.

Slow the attribution: Separate person from situation

Avoid trait judgments of dissenters. Slow your social attributions and treat observed behaviors as context-dependent.

- Disconfirm your feed—add credible challengers to your sources.

- Run a base rate check before key decisions.

- Slow attribution—separate actions from character.

- Label the effect in real time: “I see this often, not everyone does.”

- Keep a “consensus log” to track claims and outcomes.

- Use structured sampling: check three independent outlets.

- Ask experts for priors and uncertainty ranges; reject claims of perfect unanimity by others.

- When stakes are high, default to “verify, then act.”

- Share your method, not only your view—model epistemic hygiene.

- Remember: the consensus effect is predictable; your defenses can be too.

High-Impact Takeaways for Power, Persuasion, and Control

Power plays often hide behind broad statements of public agreement—treat those claims as tactics, not truths. Short, deliberate checks stop manufactured pressure in its tracks.

Remember: Perceived consensus ≠ real consensus

Foundational and modern studies in social psychology repeatedly show people overestimate how many others share their view. That mismatch is the lever manipulators use.

When you hear “everyone agrees,” pause. Demand numbers, samples, and methods before you concede social ground.

Audit influencers’ incentives and data trails

Follow money, timing, and account patterns. Track whether loud voices also profit if you act.

Core rules:

- Rule 1: Perceived consensus is a persuasion asset—treat it like an ad claim, not a fact.

- Rule 2: The false consensus effect is the default; your defense must be deliberate.

- Rule 3: Follow the money and metrics—audit influencers’ incentives and data trails.

- Rule 4: Require source transparency and reproducible numbers before you comply.

- Rule 5: In social psychology, identity cues hijack reasoning—strip them out to see clearly.

- Rule 6: Prioritize original studies, not screenshots; value methods over narratives.

- Rule 7: Ask, “Who benefits if I believe ‘everyone agrees’?”

- Rule 8: The effect is predictable—so is the antidote: base rates, sampling, and slow thinking.

Conclusion

The gap between what you feel most people think and the real data is where influence gets manufactured.

You now see how easily people mistake noise for consensus. Classic sandwich board findings and experimental social psychology work show many who agreed wear a sign then assume others would do the same.

Across journal experimental reports, Frontiers in Psychology cross-cultural examination false studies and modern feeds, the false consensus effect appears again and again. The boundary between perception attribution and proof is where manipulators operate.

Your edge: verify base rates, diversify inputs, and slow high-stakes judgments. Treat “everyone agrees” as a claim, not a conclusion—make them show the data.

Want the deeper playbook? Get The Manipulator’s Bible – the official guide to dark psychology. https://themanipulatorsbible.com/

FAQ

What is the false consensus phenomenon in social psychology?

It describes how you tend to assume your beliefs, preferences, and behaviors are common. Social perception and attribution processes lead you to project your views onto others, creating a biased sense of agreement that shapes decisions and group dynamics.

Why does your mind default to thinking others agree with you?

Motivational drives like ego defense and the need for certainty push you toward that belief. Selective exposure to similar people, cognitive availability of your own views, and heuristics that resolve ambiguity all make your perspective seem normative.

How did classic experiments demonstrate this bias?

Research by Thomas Gilovich, Lee Ross, and colleagues used hypothetical dilemmas and real choice tasks—like asking whether someone would wear a sandwich board—to show that people overestimate how many others share their choices and trait inferences.

How do social media and echo chambers amplify perceived agreement?

Algorithmic feeds and homophily concentrate like-minded content, boosting salience and making agreement appear more widespread. This perceived consensus inflates polarization and skews your sense of public opinion.

Can perceived consensus be weaponized in persuasion or politics?

Yes. Tactics such as astroturfing, testimonial floods, and manufactured social proof create the illusion of mass support. Inflating norms pressures dissenters and increases conformity in marketing, politics, and group persuasion.

What signs indicate you’re being nudged by a manufactured consensus?

Watch for rapid unanimity claims without data, coordinated praise from unclear sources, shaming of dissent, and repetition across channels. Those are red flags that consensus may be engineered rather than real.

How does this bias affect issues like climate change perception?

You may overestimate local agreement or assume polarization where nuance exists. Manipulators can polarize debates, then claim majority support to silence counterviews, producing pluralistic ignorance about real public opinion.

Are there cultural differences in how strongly people show this bias?

Yes. Cross-cultural studies, including research published in Frontiers in Psychology, find variation: individualistic contexts often show stronger projection of personal beliefs, while collectivist settings may display different patterns of social conformity and attribution.

What practical steps can you take to counteract this bias?

Deliberately seek diverse sources, ask for base-rate data, and slow your attributions by separating situational factors from personal traits. Precision checks and targeted counter-exposure reduce egocentric projection and increase accurate judgment.

How should you evaluate claims of widespread support from influencers or advertisers?

Audit incentives and data trails. Verify sample sizes, check for paid testimonials or bot activity, and look for independent polling or reproducible evidence before accepting apparent consensus as real.